Walter Mehring shared several photos from his time as a counselor on the Nature Camp Alumni facebook page – and then agreed to do a little story telling for us here.

So here we were: a girl counselor, half a dozen bedraggled campers and me, soaking wet, lost in the George Washington National Forest, and our breakfast was, at that moment, being served back at Camp, whereever that was. It seemed like we had been walking down hill from Whetstone Ridge forever…

How did I get into this mess? It all had started the summer before, when my brother, Peter, then the Nature Camp Director of Instruction, asked me if I would come teach at Camp. He thought my skills at doing things with nature as opposed to knowing things about nature would be a valuable addition. That year, I taught properties of various local woods and how to safely and effectively use wood working tools like axes, knives and chisels. After Camp, I had the opportunity to spend several months living off the land and reefs of Vieques, Puerto Rico with a spear gun and Ewell Gibbons’s book, Stalking the Blue Eyed Scallop. When I returned to Camp the following summer of ’72, Colonel Reeves’ first year as Director, we decided I would continue my “hands on” approach by teaching a class on basic survival skills and local wild foods. To add some immediacy to the class, there would be a final test: one morning, late in the second week of each session (before we’d eaten breakfast!), the Colonel would announce that “our plane had crashed,” We were then dropped off somewhere in the forest and were left on our own for 24 hours until we rescued ourselves. Each camper was allowed to take only the clothes they were wearing at the moment of the “crash.” I also took an aluminum pot and spoons.

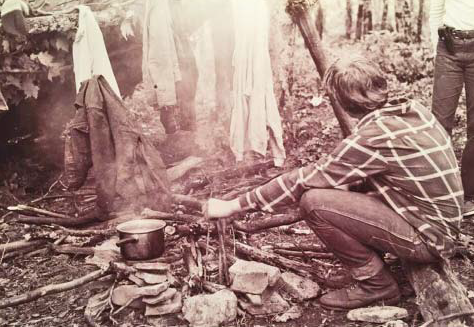

It was a lot of fun, at first. We’d practiced making shelters out of hemlock boughs, but the weather was warm and clear, and the extra work and destruction seemed unnecessary. So we foraged as we hiked and looked for a camping spot for the night with spring water, adequate dry wood, and shelter from the wind. Plant foods included greenbriar, chickweed, wild mustard, wood sorrel, plantain, wild lettuce, wild onion, violets, lambs quarters, Canadian ginger, grape leaves, fern fiddleheads, rock tripe lichen, stinging nettles, and assorted berries. Animal foods included crayfish, and dusky and seal salamanders from the creeks. On one hike we caught a rattlesnake, and caught a nice big fish by hand fishing. What we foraged went into the pot and got boiled. Some sessions ate better than others. The slim picking dinners got special names. One meal that was mostly stinging nettles and rock tripe was christened “Green Grunge”. Another that was seasoned with a baby bluejay was named “Bouillon Bleu.”

Mostly campers ate what they gathered with great cheer and fortitude. A few elected to fast for the duration. A few others threw up in the bushes. Two foods that I’d read were edible but seemed to cause problems were boiled young jewel weed shoots and raw daylily tubers.

The campers had learned to make fire without paper -2 matches allowed. So, as nightfall approached, we foraged for dryish firewood. Lower branches of hemlocks tended to be dead and dry and were easily snapped off. Three fallen saplings were slowly fed into the fire, small end first. 25-foot saplings would last the night. As darkness closed around us, the orange fire and bright sparks gave welcome warmth and security, while the rotting root ball ends of the saplings we were feeding into the flames glowed eerily with green phosphorescence in the dark beyond the circle of firelight.

Mostly, we were accident free. A camper or two huddled a little too close to the flames and partially melted their shoes. Freeman Jones sliced his hand with a knife trying to make a spear for a rabbit hunt.

A little after midnight, survival got real.The warm evening temperatures plummeted and we were drenched with cold soaking rain and wind that quickly reduced our warm fire to a few struggling coals and left us shivering in the dark. To avoid hypothermia we sat packed together in a line, back to belly, through the long night to conserve body heat. It was a long wait for the slow glow of dawn.

With first light we got moving down the mountain to warm up, in eager anticipation of Camp breakfast. But, as the morning wore on the forest never seemed to end, which is where this story begins. Eventually we did hit Rt 608. We’d taken the wrong ridge down and were heading toward Buena Vista rather than Camp. We got back to Camp in time for lunch rather than breakfast. There were cheers when we finally showed up. Rumor had it that Colonel was on the verge of calling out rescue helicopters.

Looking back, I’m surprised the Colonel let the class continue, especially after that first Whetstone Ridge trek. We had no cell phones in those days so there was really no way to get in touch with Camp except to show back up again after 24 hours. Liability risk seemd pretty high, but the good Colonel let me continue the class for the rest of that summer and the next. I believe Freeman Jones continued the class after I left.

I hope the class was good for my campers. I know it was good for me. After college, I had no clear idea of what I wanted to do next with my life. Shortly after my last Camp session, I emerged from my shack in the woods where I was living and burst into tears. I suddenly realized I was going to become a teacher. For nine years after that, I taught wilderness survival skills as a Life Science teacher. After that, for thirty years, I taught wilderness survival skills as a counselor and marriage and family therapist.

I have loved it all!